Ghosts in the Darkness: The Man-eaters of Tsavo Bridge and H.P. Lovecraft

Something was there. Watching. Biding.

In the pitch black of a Kenyan night, the sleepless workers listened and held their breath. Silence had fallen on the British railroad construction camp. A fear that lurked in every shadow; in every gasp of wind.

The sun had set several hours ago. The nightmarish beasts hunted at night.

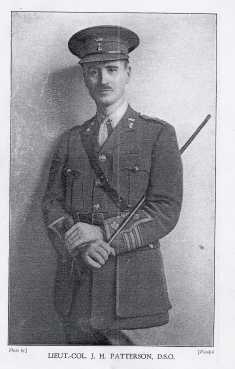

Lieutenant-Colonel John Henry Patterson, the man who led the Kenya-Uganda Railway project, was petrified. Whenever the moonlight was weak, they would stalk their human prey. A waning gibbous soldered above, in a few days the moon would be dark and the specter of death would follow. If there was a hell, Patterson and his large troop of Indian workers were trudging through its trenches.

When the deaths began in March of 1898, there was talk of foul play. Patterson had served the British Army for 14 years – he knew how to dispense justice. One man killing another or even two was not unheard of. But the third; he had been a good man and well-liked by all.

The third death convinced Patterson that a primal miasma was present. It was not that the man was kind in life, rather the deplorable scene of his death. In the cruel embrace of a tree in the bush, gore climbed the leaves in layer upon layer of carnal, human horror. The wanton remnants of a good man. His head and bones were spared.

No man could have done such an act; no, this was beast. Ghosts in the darkness.

Patterson had seen many new species in his time in Africa. In his book, The Man-eaters of Tsavo, Patterson elucidates encounters with a wildebeest that faked its own death, a herd of wild Dionysian zebra, packs of wild dogs, hippopotamuses, a red spitting cobra and rhinoceroses. But nothing in his experience was as cruel as these manifestations of evil; the demons called Ghost and Darkness.

Patterson knew he would have to leave the camp. He was scared, but he was clever. Hundreds of traps; scaffolds soaring above for a good shot. A Martini-Enfield bullet in his hand; he stroked the case of the little projectile. Watching. Biding.

It had been almost nine months since these attacks began. So many had died. The cries of the unlucky chosen haunted the waking nightmares of the railroad workers. The howls were heard in every camp on the winding railroad as the sacrifices were dragged from safety. How quick that silence returns. That perpetual terror lingers like vultures in the hearts of men. That fear that drives mankind to sickness and rage. That profane whisper into the void. That endless night.

The end waits for Patterson. Out there, in the darkness.

Movement. Quiet strands of grass ebb and flow as the unnatural fiends come closer.

Lions. Two maneless, male lions prowled the dark grounds outside the bomas, or fences made of thorn bushes. The imported labor for this British enterprise was almost entirely from the Indian Subcontinent – dubbed “coolies” by their British Army overseers. The “coolies” provided ample nourishment for the two devils that prowled beside their camp.

Patterson, his father a Protestant and mother a Roman Catholic, knew there had to be a God. A heavenly father to justify this unholy, abominable circumstance. A reason for the madness.

Patterson knew he must serve his station to protect his workers for both reasons of duty and the desire to save himself from devouring. Construction had stopped for weeks; the railroad workers coagulated in their tents and told tales of the horror that stalks outside the camp walls. That was how the lions received their names: Ghost and Darkness, as demonic beasts were easier to rationalize than two cats predisposed to human flesh.

Patterson placed the bullet into his .303 caliber Lee Enfield rifle and pointed at the darkness. He could not see well, the moon was weak and the grasses were tall.

There it was, white in the pale light. Lumbering in silent deliberation. Blood-starved and moon-drunk, the hellish cat crawled closer. Torchlights from a distant fire flickered across his amber eyes. Patterson took one last breath as the creature approached. He held it for the longest second of his life and fired into the darkness.

Welcome! To the first in a three part series pouring through the life of HP Lovecraft. Yay!

So, what do two murderous lions, a terrified English Lieutenant Colonel, and H.P. Lovecraft have in common?

As always, we must start with the beginning to answer that question.

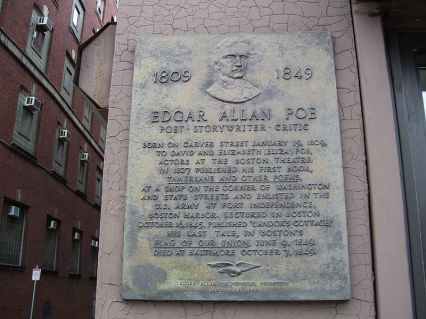

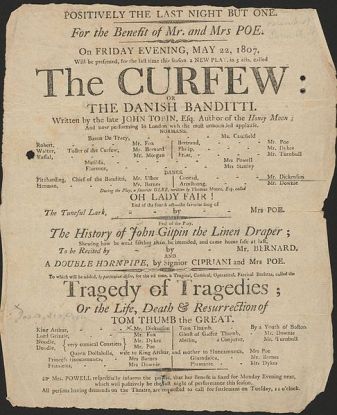

On a warm June day in 1889, two lovers stood before an altar at the Cathedral Church of St. Paul in Boston. After a long courtship, Winfield Scott Lovecraft was going to marry Sarah Susan Phillips. Now in their mid-thirties, they finally consummated their relationship before the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts. This was one of Winfield’s happiest day; he did not know of the ghosts that sulked in the darkness of his mind.

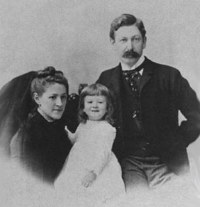

Howard Phillips Lovecraft was born on August 20, 1890 at 194 Angell Street in Providence, Rhode Island. His parents were overjoyed at their good fortune. Having married so late compared to the norm of the time, they were deeply fearful of miscarriages and stillbirths. But their miracle child was born and HP Lovecraft began.

There’s the young Lovecraft family. Yes, the longhaired, dress-wearing toddler in the middle is HP (quite normal for the time)

Winfield Lovecraft was a traveling salesman – pawning off rare metals and jewelry for Gorham, Son & Company. It was on one such occasion, in Chicago, where Winfield Scott began to see something stranger than reality.

HP was only three when his father was diagnosed with psychosis. The elder Lovecraft disappeared into Butler Hospital, a victim of his insanity. He would remain there, interred under a comatose veil, for five years until July 19, 1898. The doctors told his family that Winfield was paralyzed and passed away without pain. Despite the young HP Lovecraft’s innocent hopes, evidence points to an advanced form of paresis – a type of neurosyphilis – killing his father while depriving him of his sanity. Echoes of a former life, shrouded in unspoken obscurity.

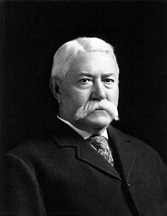

HP was left to the care of his mother, her two sisters Lillian Delora and Annie Emeline, and his charismatic maternal grandfather – Whipple Van Buren Phillips.

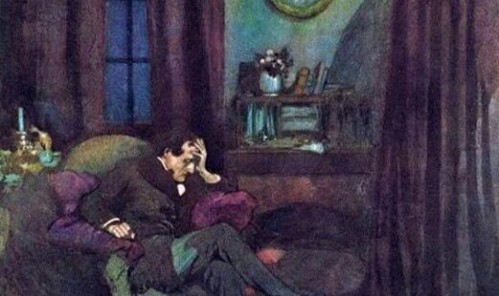

Following his father’s death, Lovecraft became incredibly reclusive. His youth was sequestered by the overbearing hand of his mother Sarah. Night terrors, what would later be diagnosed as a rare form of parasomnia, struck him often throughout his childhood.

These waking nightmares dwarfed his human concept of what was dreaming and reality – fueling works like The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath. Hideous beasts with black, membranous wings flew without sound over the sleeping Lovecraft. These creatures with barbed tails, used to “tickle” their victims into submission, he dubbed them “Night-Gaunts.” They would appear from time to time in his writings; like half-remembered dreams.

Lovecraft regarded the murky nature of his dreams and reality in a letter to his pious friend, Maurice W. Moe:

“Do you realise that to many men it makes a vast and profound difference whether or not the things about them are as they appear?… If TRUTH amounts to nothing, then we must regard the phantasma of our slumbers just as seriously as the events of our daily lives…” (15 May 1918)

Lovecraft was often sick and bedridden; a forced isolation that hung over him his entire life. Indeed, he withdrew from school at the age of eight for an entire year due to various supposed illnesses. The stifling clasp of his mother’s controlling hand was more likely to blame.

Life in the Phillips household was profoundly secluded. Sarah Susan, HP’s mother, called him “grotesque” and cloistered him in the house – forcing him to become a veritable night-owl. Another peculiarity that became habit by his teens.

In spite of his domineering family, Lovecraft would create make-believe games for the neighborhood’s children. He would continue to imagine a wilder world with his young cohorts until the age of 18, when he reluctantly let go of this “childish” practice.

Despite his weak disposition, HP was a precocious child and a voracious learner. He was reciting poetry by the age of two, and published his own hectographed prints for The Scientific Gazette when he was eight. Homer’s epics, gothic horrors, Arabian Nights, Bulfinch’s Age of Fable – all of these fell prey to the young Lovecraft’s curious gaze.

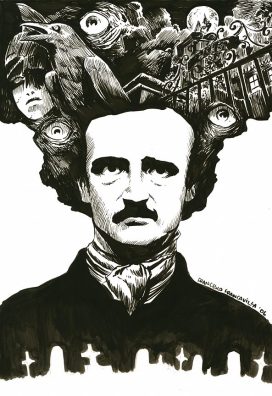

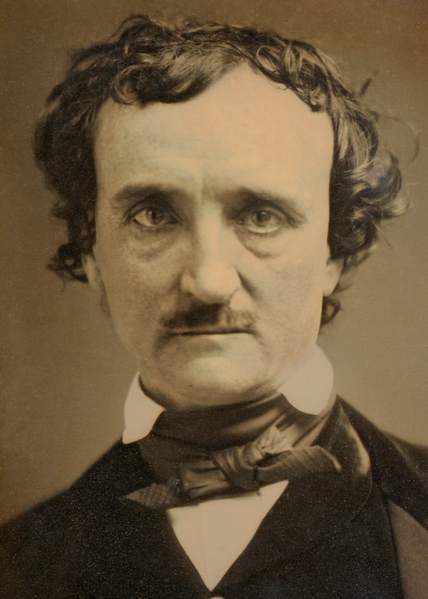

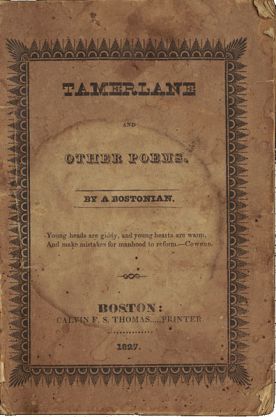

Even at a young age, he had a materialist mindset. He delved into astronomy and chemistry. He essentially self-educated himself in lieu of public schooling. HP explored literature and prose – drawing from the works of Edgar Allan Poe (for those of you who read the last post) as he gradually ventured into the literary world.

In 1904, as HP was wading through puberty, his grandfather and patriarch of the Phillips family, Whipple Van Buren, died. In the wake of his passing, the Phillips suffered gross mismanagement over their father’s estate. Due to financial desperation, the three sisters and HP moved to 598 Angell Street, just down the road from their former home.

HP grudgingly continued his schoolwork, but in 1908 experienced a “nervous breakdown” that forced him out of public education. He would never return to Hope High School (a delightfully ironic school name for Lovecraft) nor did he ever get a diploma. At the age of 18, he began his long reclusion.

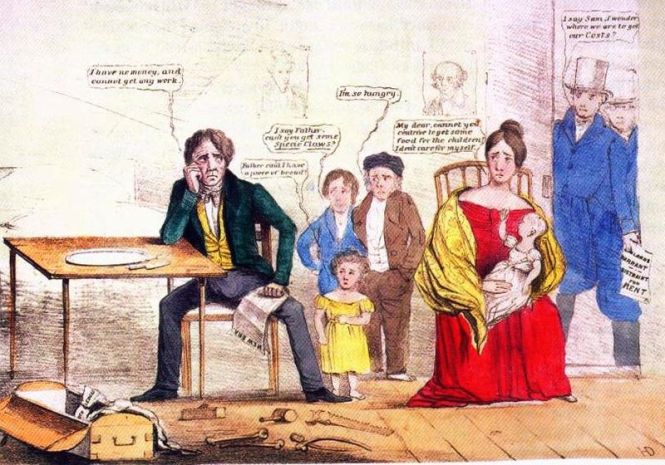

For five years he languished in silent solitude; his social contacts were nil and likewise for any romantic prospects. He wallowed in selfish deliberation and quarreled with inner demons alongside external frustrations. For five years he sat – “unemployed, antisocial, the family fortunes declining” – he harbored a steaming hatred that festered like meat in the sun, ultimately resulting in misguided racism (though he was pretty racist, I am not going to sugarcoat that). He was also a far-right wing conservative largely to of his upbringing among the traditionally-minded Phillips sisters.

In the coldest hours of night, Lovecraft hunted through the darkness. He loathed the world and himself. He later recalled in a letter that “science was the only thing that kept me from committing suicide…”

But the night does end, and the dawn is beautiful.

In 1913, a pulp magazine called The Argosy was hosting a peculiar letter writing war. A young and particularly persnickety epistolarian (one who writes letters – Collins Dictionary), HP Lovecraft, was complaining of the crass “insipidness” found in the love stories by one of the magazine’s contributors, Fred Jackson. The debate between the two was so tenacious and publicized that it got Edward F. Daas, president of the United Amateur Press Association (UAPA), to notice. In 1914, after five years of nocturnal wanderings and self-imposed isolation, President Daas invited Lovecraft to join.

HP was ecstatic. He had hundreds, if not thousands, of scrawled papers strewn about his home. Stories glinted from hundreds of sources – from the tales of his childhood to contemporary archaeological digs. Lovecraft had so much to say, and finally had a means to do so. He set to work.

Lovecraft published his first short story through the United Amateur two years after he began his correspondence with the editors. The Alchemist appeared in the November 1916 edition with limited success. The protagonist of the dark tale, Charles Antoine de C– (not a typo!), is the last in a line of a cursed dynasty. Many years before, his ancestor killed the evil wizard Michel Mauvais. The warlock’s son, Charles le Sorcier (if you know French then you realize how asinine these names), cursed his father’s killer – every male heir would perish at the age of 32. As the story progresses, good Charles wanders in the ruins of his family’s castle, alone and terrified as he recently celebrated his fateful birthday. Happening across a trapdoor, a figure creeps out and nearly kills Charles, only getting killed himself in the process. To good Charles’ surprise, it was the evil Charles who nearly killed him – having discovered the elixir of life to sustain himself while ensuring the promise he made to his father.

Inherent guilt dominated many of HP Lovecraft’s short stories; cursed families, fated doom, etc. “The Rats in the Walls,” “The Shadow over Innsmouth,” and other works all exhibit this theme. HP’s self-loathing would never truly leave him, and his obsession with fate and guilt may easily have grown out of his fraught childhood. Indeed, The Alchemist began in drafts as early as 1908, eight years before publishing – the year Lovecraft had his anxiety attack, the year he quit school; departing for nebulous isolation.

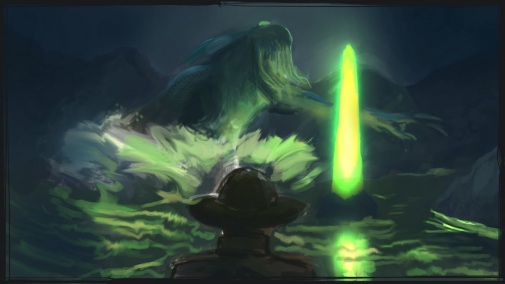

Another crucial and existentially disconcerting concept for Lovecraft was the inconsequentiality of humanity. As the years wore on, pantheons of eldritch gods littered the known and unknown universe in HP’s dystopian realities. Most were malicious, manipulative, psychotic, and vast beyond all imagining, but they all held one trait in common: they did not care for the tiny organisms on our pale blue dot – as a man regards a microbe.

This theme crescendos later in Lovecraft’s life, specifically through the Cthulu mythos (that will be the third part of this series), but began with a short story written only a year after The Alchemist: Dagon. The account follows a morphine-addled mariner who finds himself adrift in the Pacific Ocean after a German ship sank his last vessel. After several days of following the current, he woke upon a vast, silty landscape; his lifeboat striking land sometime the night before. The mariner ventures out after he waits for the ground to dry – hypothesizing this land to be a massive, abyssal slate that burst forth from the murky depths due to recent volcanic activity on the seafloor. After two days, the seaman peers upon an “immeasurable pit” circling a white monolith with etchings of aquatic beasts and strange humanoid fish-men. He hears movement, and one such beast exploded with tremendous speed toward the monolith, groveling before it and prostrating in primordial prayer. In terror and confusion, the mariner flees, encounters a storm on his lifeboat, and wakes in a San Francisco hospital.

Near the end of his tale, the mariner bleeds into existential terror:“I dream of a day when they may rise above the billows to drag down in their reeking talons the remnants of puny, war-exhausted mankind – of a day when the land shall sink, and the dark ocean floor shall ascend amidst universal pandemonium.” (Lovecraft 19).

With this sudden success, HP Lovecraft was feeling more secure in his writing and immersed himself in the culture of weird science, which had appeared in the late 19th century out of science fiction, horror, and romantic literature. His prodigious letter-writing convinced him to establish his own magazine, The Conservative, in 1918. He published many of his own essays through his journal, but they were joined by poems, critiques, political and social commentary alongside new short stories from HP’s expanding circle of colleagues.

Despite this literary blossoming, tragedy always followed in Lovecraft’s steps. In 1919, Sarah Phillips was committed to Butler Hospital for hysteria and depression. Just like her husband, she was incarcerated in a locked room and lived in a half-mad world brought on by years of unchecked paranoia. Also like her husband, she would never leave the sanatorium; Sarah Phillips died on May 24, 1921, due to complications from gallbladder surgery.

In this period of HP Lovecraft’s life, he published a flurry of short stories inspired by the macabre tales of Edgar Allan Poe. Indeed, this is considered the first part of his literary evolution. From 1905 to 1920 – from all of the tales he read in his youth and the material gathered from years of research and arcane curiosity – the young author languished in his “Poe stage,” inspired by the gothic poet and essayist Poe. For those fifteen years he wrote 22 stories, most penned when his mother first left for Butler hospital. In that time of grief, the fear of fated insanity or a inherent guilt plagued his mind. His stories held him to this earthly anchor. Creativity required sacrifice.

Only a few weeks had passed since his mother’s funeral. Lovecraft was alone, his mother had (over)protected him and was the closest relationship he had; but she was gone. They had sent letters in those last two years to one another, kind words and concerned questions unanswered. Lovecraft knew he must steel himself, his heartache and depression would not pay for dinner. So, HP left for Boston, where he found opportunity at an amateur writing convention.

At this hub of intellectual activity, HP Lovecraft came across something he never thought he would find – a love of sorts. While in Boston, Lovecraft happened upon Sonia Greene, a successful hat shop owner of Jewish-Ukrainian descent. If you remember the racism that cropped up fairly often in Lovecraft’s works, then this is especially significant for the traditionally-minded Phillips family. While HP’s aunts disapproved of the relationship, he was platonically infatuated with her. Sonia Greene was a divorcee and seven years older than HP, but the fragile writer did not care how society judged them.

From left to right: friend and later communist foe Rheinhart Kleiner, subject of courtship Sonia Greene, and the ever-sociopathic HP Lovecraft.

Two years after his mother died, Lovecraft faced his darkness. From romantic macabre, he had exploded onto a new literary arena. He stood at the precipice, staring into the void. In 1922, Lovecraft made two choices. The first was to marry Sonia Greene. The second, was to take another step forward – into the unknown future – to evolve out of his gothic trappings and into a realm dominated by the power of dreams. With a heavy past shackled to him, HP Lovecraft took a chance. He shot in the darkness.

Back to man-eating lions.

Lieutenant Colonel Patterson did not leave his tower that night. Even two stories above the Kenyan savannah was not far enough to keep the man-eaters away. The early sun crept above the horizon as Patterson looked down at the tanning landscape. River She-Oak and Baobab trees sprouted sporadically, like sprawling ships in a sea of yellow grasses. Patterson peered carefully through the thrushes, a heavy indentation made a dark impression not too far off, but the beast who made it was gone. Something else was there, spatters of red slashed the stalks of wild grains – the demons could bleed.

The lions had been getting cocky with their most recent attacks. At first, Ghost and Darkness would sneak into a railroad camp, take their prize, and then disappear into the bush. Now they were dragging their victims only twenty or thirty yards before feasting on them. They also attacked different construction camps for each hunt; surprising the guards along the railroad. No one expected beasts to outsmart humans. Now the lions were growing complacent in their invincible invisibility.

The night after they shot Ghost was darker. An emaciated gibbous moon glowered above the oceans of savannah grasses. They walked in complete silence, crunching the dry leaves that covered the grassland floor. Patterson motioned for them to stop.

They listened to the land around them; the wind sounded like ocean waves as it crashed on the pale fields around them, branches cracked and gnarled in the distance, vibrations from a thousand different species reverberated through the soil. Patterson was deathly quiet. He knew they were not alone.

A single predator was stalking them. Sniffing the air, it circled the two hapless humans in silent shadows.

Patterson caught hints of the lumbering monstrosity – movements in the bush that seemed natural, but the wind does not track its prey. He knew where the beast was.

Pointing his gun, he aimed at nothing and prayed it was something. He thought he could hear breathing, the fall of a paw with unheard finesse, a deep guttural vibration called out from the bush. Once more, he shot into the darkness.

As the discharge ringing faded from their ears, the two humans heard roaring. Thrashing and growling, the maneless lion sprawled out of the bush. A single circle of red marked its shoulder, the entry-wound was a very lucky one. Wrestling with the grasses, the felled devil expired as it let out its last breath.

It took eight men to carry the lion’s corpse to the camp. It measured 9 feet and 9 inches and two bullet holes showed Patterson had shot it in the back leg before killing it with a bullet to the shoulder, which penetrated straight to his heart.

Without its partner, the other male Tsavo lion was handicapped, but just as ferocious.

Not long after the man-eater’s colleague was killed, Patterson knew the other would not leave its taste for man-flesh. He had built up another live goat trap to fool the lion, though these ambushes often proved to be a long shot. Despite how obvious the humans seemed behind their thornbush walls, the Darkness took the bait.

The first bullet struck the lion with surprising ease, but Darkness spirited away and began a wild chase through the bush. Eleven days passed while the hunting parties swarmed in the wide, yellow fields. Eleven nights and Patterson soon found himself in a familiar situation. The grasses ebbed with the confident deliberation of a predator stalking its prey. Patterson knew his follower would try to attack without warning, and the Lieutenant-Colonel had prepared for this ambush.

The man was given a choice, fight or flight. He chose to rush the nightmare, and the hellish beast fled, but not before receiving another bullet to remember.

The following day, Patterson shot the maneless lion three more times, crippling it. The Darkness fled again, its blood decorating the grasses in a neat trail. At the end of the odorous path was a tree, the carnivorous cat nursing its wounds among the gnarls.

Patterson walked with calm focus. A Martini-Henry carbine guarded tightly before his chest. Despite his guile, the Darkness smelled him on the breeze; his muscles taut with savage rage.

Patterson had no hesitation, he shot the lion once in the chest and reloaded. No effect, the lion tore through branches while cascading down the tree. The man shot again; Darkness growled and gurgled and bit through bark as it tried to reach him.

He was close; even if Darkness was bloodied and ragged, the beast was so terrifyingly close. He loaded another bullet into the chamber of his rifle next to his heart. He clicked it in with a quick lever action beneath the trigger before returning his index finger to its post. He aimed; Darkness howling through wheezing roars in the low branches of the tree above him. Patterson fired one last time.

The nightmare was over. Nine months had passed since the terror first swallowed his isolated railroad construction camps. Nine bullets in a dead cat and Lieutenant Colonel Patterson had fired every one. He had gone toe-to-toe with unknown shades in the night, shared oblivion with man-eaters who only knew ravenous, insatiable hunger. In front of an impossible force that ripped through humans like lame wildebeest, Patterson stood his ground. Like Lovecraft, he chose to take that step forward into the void; onto that unseen ground, into the wide and unknown future.